The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece

“What now remains of these victories of yesteryear?

A woman’s work. Yet nothing is more clear

Than that the needle, in the last resort, is mightier than the spear.” (Jean Berthot)

The one date familiar to all British school children (and maybe North American children too) is 1066, the year William the Conqueror invaded and became ruler of Great Britain. No written records remain; the boats and weapons disappeared long ago; but there remains one physical record of that battle – the Bayeux Tapestry.

I’m planning to visit Normandy and Brittany this winter and hope to visit Bayeux to view the tapestry, so I decided to read The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece by Carola Hicks.

The Bayeux Tapestry is 230 feet long and 20 inches tall and was embroidered in wool on a linen background. Humble materials, but if it had been made of silk, gold threads, and gems, it wouldn’t have survived as it would have been cut up and stripped of its valuables. In contrast, the tapestry has led a charmed life, surviving in spite of a long series of moves, wars, and other disasters. More modern fabrics and dyes wouldn’t have survived either, but these were materials built to last. For example, the entire fleece was dyed, rather than the individual skeins of yarn.

There is considerable debate as to who initiated the tapestry, but it was probably a woman, either the wife of King Harold of Great Britain or King William of Normandy. And the handiwork would all have been done by women.

The involvement of women has caused consternation and debate for centuries. Could women’s handiwork actually be viewed as a historical document? Could a woman have actually been in charge and designed such a product – surely it required a male artist to design the 70 different scenes? The debate continues today as we contrast high art (paintings and sculpture) and handicrafts (weavings and pottery).

Another topic of debate is the quality of the work. For many years, the designs were viewed as primitive and poorly done. In fact, an engraver added in shadows and 3-D effects before publishing drawings of the tapestry. The characters are often portrayed in somewhat stilted poses, but this is deliberate as the actors were speaking in a visual language that would have been well understood at the time. Touching one’s face was a sign of grief or mourning. A closed fist with only the little finger pointing indicated an eavesdropper, while a clenched hand with one finger raised was a sign of supplication. By the 20th century, there was a new-found appreciation for the simplicity, expressiveness, and lack of realism. Advertisers have adopted similar techniques for marketing purposes. The flow of individual scenes can be compared with cartoons and films.

The tapestry, perhaps because of its longevity, has become an icon and been rapidly adopted over the centuries for propaganda purposes. Napoleon, who had plans to invade England, put the tapestry on display in Paris, where it stimulated a play that later toured the army encampments. During World War II, the Nazis were determined to obtain the tapestry, not only because it represented a successful invasion of Great Britain but because they viewed the Normans as natural ancestors of the German race.

History, culture, art, and communications all join forces in the Bayeux Tapestry, making Carola Hicks’ book well worth reading.

See Also

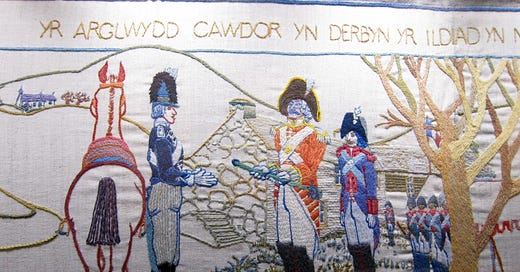

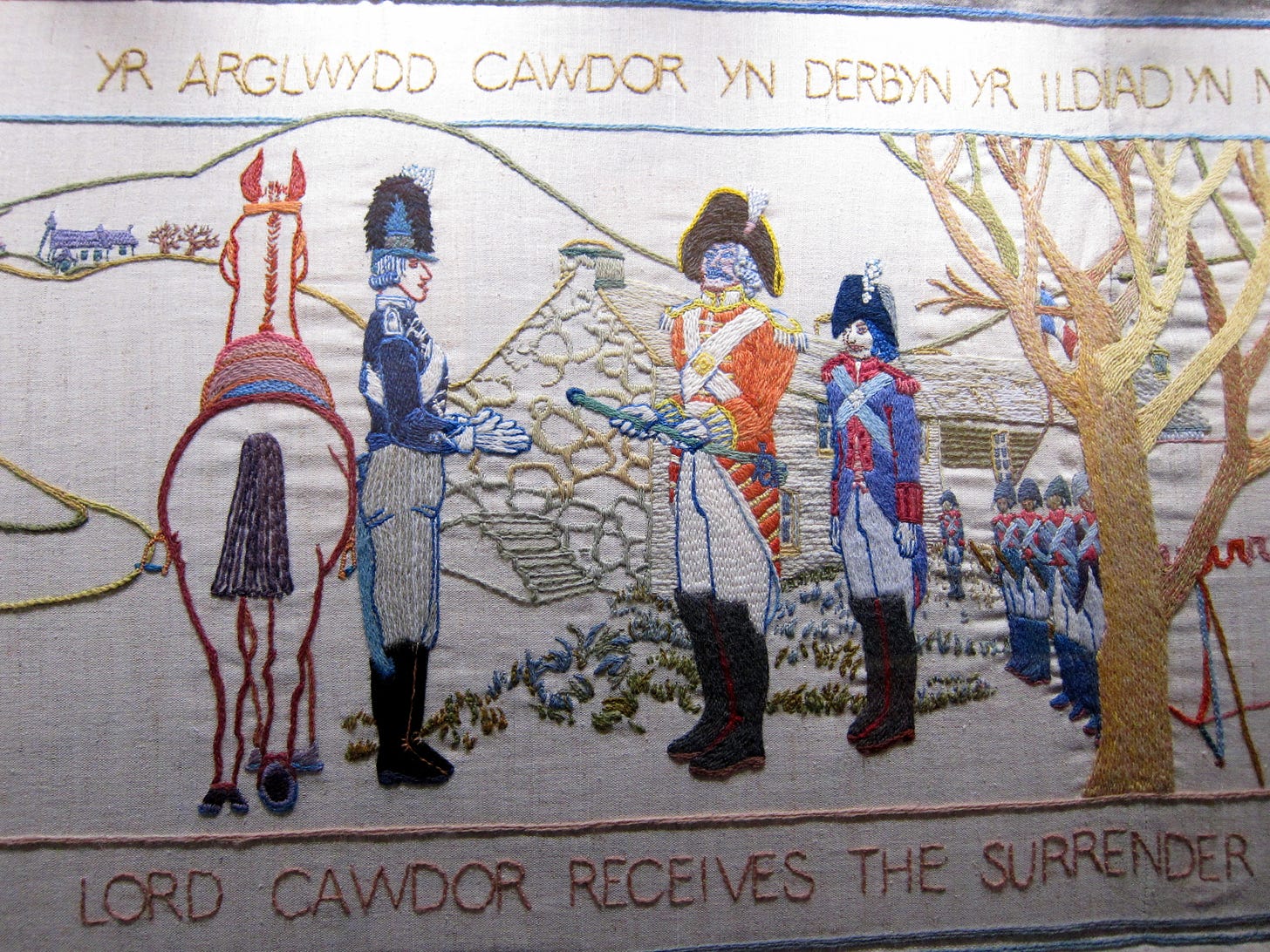

The Last Invasion Tapestry, Fishguard, Wales, represents the last time the British mainland was invaded. The plan failed completely.

All photos are of Fishguard’s Last Invasion Tapestry.